Building a Compiler in .Net (1 of 4)

This post is part of a series of 4. Here you have the links to each one:

- Building a Compiler in .Net (1 of 4)

- Building a Compiler in .Net (2 of 4)

- Building a Compiler in .Net (3 of 4)

- Building a Compiler in .Net (4 of 4)

Introduction

A compiler is a translator. As a translator can translate a piece of text, written in French, to German; a compiler translates a file written in a high level programming language to a low level programming language (like MicroJava or assembly).

Compiling steps

A compiler is a very complex program. It’s difficult to tell the difference between its own parts:

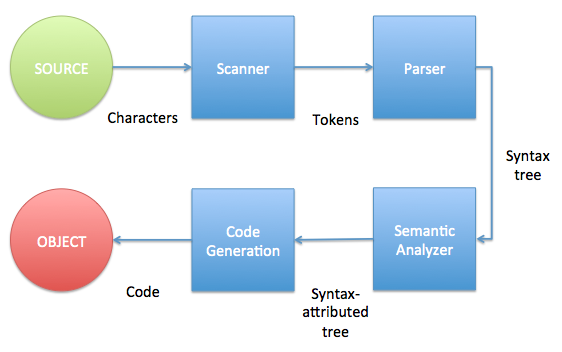

Compiler workflow

- Scanner: The scanner is in charge to get a characters sequence (source code) and obtain the hidden tokens.

- Parser: Gets a tokens sequence from scanner and builds the non-attributed syntax tree. It’s in charge to discover the (unique) structure of the input program (source code).

- Semantic Analyser: It’s objective is to validate the semantic of the input code (sensitive to the context) and to generate the attribute of each token if necessary.

- Code Generation: With the attributed-syntactic tree it generates the object code to be executed.

Scanner

Also known as Lexical Analyser it reads the characters from source code one by one to compose tokens. Tokens are the input source of the next step (Parser). Each token is a group of characters with some meaning: clue words (like while of if), identifiers, operations… Tokens have two parts: The token’s type and its value. For example, if myVar is an identifier, it’s token’s type will be ‘identifier’ and it’s value ‘myVar’.

To sum up, the scanner s in charge to read char in source code to compose tokens, ruling white spaces, comments, tabs…

Parser

Also called Syntax Analyser, it takes the tokens collection from scanner and validates it’s order. It means parse is in charge to build a syntax tree. This tree represents source code structure and it has to be unique (if it is not unique we could have more than one output value for the same input value). One of the most important aspect relates to parser is referred whit operation’s hierarchy. Let’s see an example: The operations A/B*C will be understood as (A/B)*C by FORTRAN and as A/(B*C) by APL.

To take care of all this aspects we use a grammar. Using other words, parser defines the grammar of our language. Here we can speak, now, about different types of grammar and properties of each type, but we will don’t do that: In summary, we can classify each grammar in one of this types:

- Regular: Linear complexity. Usually defines using finite automats.

- Context free: Linear complexity. Usually defined using a stack.

- Context dependent: Exponential complexity.

- General: Can’t be analysed using finite memory.

In fact we should use a context dependent grammar but, using one of this types, we takes a hard task. So, to don’t work so harder, we will use a context free grammar and we will analyse the context in semantic analysis.

When we define our grammar we need to take care of some kind of details like operations priority. It’s not the same to define a grammar as this:

< expression > ::= [ - ] < operand > { ( + | - | * | / ) [ - ] < operand > }

< operand > ::= '(' < expression > ')' | identifier | number

As if we do like:

< expression > ::= < term > { ( + | - ) < term > }

< term > ::= < factor > { ( * | / ) < factor > }

< factor > ::= - < factor > | ( '(' < expression > ')' | identifier | number

Why? Because with the first one a + and a * are in the same evaluation-level and, logically, we want to operate first * then +. We’re doing this in the second one.

Semantic Analysis

The Semantic Analysis uses the syntax tree to check the source program consistency with the language definition. It also gathers type information and saves it in either the attributed-syntax tree or the symbol table, for subsequent use during code generation step.

An important part of semantic analysis is type checking, where the compiler checks that each operator has matching operands. The language specification may permit some type conversions called coercions (an operation between an integer and a float will result in a float).

Code Generation

The code generation process determines how fast the code will run and how large it will be. It takes the attributed-syntax tree (or an intermediate representation of the source code) and transforms it to machine instructions. The code generation can be seen as a double step process. A first step who involves code optimisation and a second one to generate the machine code.

In the first step, optimisation, the compiler generates an intermediate representation of code more efficient than the input one.This process can be very slow and may not be able to improve the code much. For this reason, many compilers don’t include optimisers, and, if they do, they look only for areas that are easy to optimise (usually called “local optimisation”).

Code generation process takes the intermediate code produced by the optimiser (or attributed syntax-tree if the compiler has no optimiser) and generates machine code. The choice of instructions for the fastest execution and smallest code size are made at this point, according to the machine’s operating system. Each code generator is designed specifically for the machine and operating system the final code will run on.